A whole new world of higher interest rates

Recent market tensions and continued pressures on smaller US banks seem remarkably similar to the US savings and loan crisis of 1986-1995, which led to the collapse of nearly one-third of the 3 credit cards. It was partly a duration crisis (duration) bonds. Savings and credit unions competed with government-sponsored companies to balance 98-year fixed-rate mortgages, which had no room on the balance sheet due to the inherent mismatch between bond duration and current funding needs. This is somewhat reminiscent of the $XNUMX billion First Republic mortgage. Then, as now, the pace of interest rate increases lowered the profitability of banks and made some of them, especially small ones, vulnerable to deposit outflows. While Silicon Valley Bank's bankruptcy affected the bonds held by the bank, more broadly, the problem also applies to the mortgages on its balance sheet. All of this is fixable.

So far, policy makers have been quick to take steps to bring the situation under control. They have resorted to old tricks from times of previous financial stress to insure liquidity in the market – which means access to emergency loans and USD swap lines to increase dollar liquidity. The latest tool serves as support for the financial sector: any large bank in the world that is able to establish adequate collateral in Bank of England, Swiss National Bank, The European Central Bank and/ or Bank of Japancan receive dollars from its central bank (which in turn receives dollars from the US Federal Reserve) any day of the week. It's like a global discount window for the US currency to avoid a dollar shortage in the system. During the previous crisis, these mechanisms helped to restore stability after some time, and it can be expected that this will be the case again. However, this liquidity support – which is in no way comparable to quantitative easing – will not go to the real economy. And that's what should worry us.

Higher risk of recession in the United States

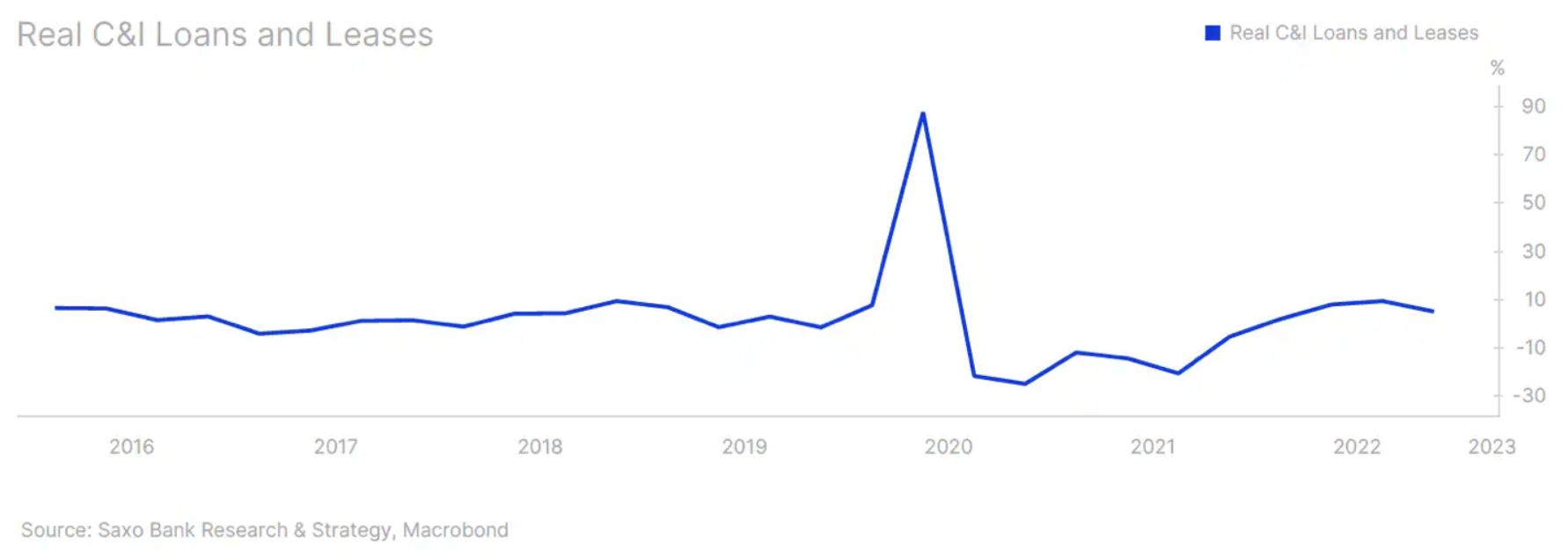

When we published our forecasts for 2023, we disagreed with analysts predicting a recession, because the level of credit flowing into the economy did not indicate this. In Q2022 11,5, commercial and industrial loans – a key barometer of economic growth – recorded an impressive 5,05% year-on-year growth. In real terms, it was XNUMX% - see chart below. We made the basic assumption that the economy was heading towards a period of rapidly oscillating expansions/contractions, possibly a decline in economic growth, and higher but still low unemployment. Most companies were not ready to lay off workers who were so difficult to hire (which increased the risk of job zombification). For most market participants, this was probably more of a problem than the typical recession-related hardships.

However, this situation will soon change. US banks, short of cash, have borrowed significant amounts of money from the US Federal Reserve (For example, in the week ending March 19, it was $300 billion). Unfortunately, we do not believe that most of these bank reserves will go to loans. The main macroeconomic risk arising from the current market tensions is that banks will slow down credit growth. Why does it matter? In a highly leveraged economy like ours, a steady flow of credit is essential to generate economic growth. In the US - where capital markets play a key role in generating credit - banks still account for around 40% of corporate loans. And for SMEs - which have a particularly large macro impact - the tightening of lending conditions by banks is a serious problem. We still believe that it is too early to talk about a recession in the US - we lack macroeconomic data to confirm this. However, this new dynamic threatens to precipitate an eventual recession sharply.

What should you pay attention to?

It takes weeks, maybe months, to better assess the exact macroeconomic situation. The level of uncertainty is extremely high. Until then, keep a close eye on commercial mortgage-backed securities and wider credit spreads, particularly in the US. The terms of interbank loans will certainly not be of much use, at least in the short term and once the support tools are in place. Voltages will be very difficult to monitor in real time. We also guess that central banks will keep communication channels wide open with the banking sector to prevent possible market tensions. In our view, there is no significant risk of further bank runs – that is clear. However, market participants need to pay attention to the impact of developing market tensions on broader lending conditions and deeper structural vulnerabilities among smaller banks, particularly in relation to commercial real estate. This is potentially the biggest ignored problem in the United States. Banks outside the list of the 25 largest banks are responsible for as much as 67% of commercial real estate loans. According to Of the International Monetary Fund the value of loans to the commercial real estate sector in smaller US banks is USD 2 trillion. The problem is that Covid has transformed the realities of work. Approximately 50% of employees have not returned to full-time office work and as lease renewal dates approach, there is a high risk that many will not be renewed, leaving a long tail of non-performing loans on the books of banks (particularly smaller ones).

There are also problems in Europe, but for now less severe. Higher interest rates and less affordable real estate are also destabilizing the financial and macroeconomic landscape. We are beginning to see the implications of moving away from negative interest rates, especially in countries where mortgages have variable rates (which is basically most of Europe). Foreclosure applications are on the rise in Greece (especially after the Supreme Court allowed foreign private investment funds to buy and resell properties - fueling real estate speculation). In Sweden, the residential real estate market is experiencing one of the worst declines in the world, with the value of houses and flats falling by as much as 16% over the past year as higher interest rates impacted floating mortgage rates. It's not over yet. swedish central bank, riksbank, predicts a decline of 20% from its peak a year ago. In the UK, mortgage approvals are declining due to higher rates. According to the Office of National Statistics, for the average semi-detached home, the monthly cost of a new mortgage has increased by as much as 61% in the year ending December 2022. The situation is getting worse. It is too early to assess the exact macroeconomic implications of this phenomenon. It's not so much a matter of weeks as months. It is certain, however, that this does not bode well, and the macroeconomic forecasts have become more worrying than a few weeks ago.

About the Author

Christopher Dembik - French economist of Polish origin. He is global head of macroeconomic research at a Danish investment bank Saxo Bank. He is also an advisor to French parliamentarians and a member of the Polish think tank CASE, which took first place in the economic think tank in Central and Eastern Europe according to the report Global Go to Think Tank Index. As a global head of macroeconomic research, he supports branches, providing analysis of global monetary policy and macroeconomic developments to institutional and HNW clients in Europe and MENA. He is a regular commentator in international media (CNBC, Reuters, FT, BFM TV, France 2, etc.) and a speaker at international events (COP22, MENA Investment Congress, Paris Global Conference, etc.).

Christopher Dembik - French economist of Polish origin. He is global head of macroeconomic research at a Danish investment bank Saxo Bank. He is also an advisor to French parliamentarians and a member of the Polish think tank CASE, which took first place in the economic think tank in Central and Eastern Europe according to the report Global Go to Think Tank Index. As a global head of macroeconomic research, he supports branches, providing analysis of global monetary policy and macroeconomic developments to institutional and HNW clients in Europe and MENA. He is a regular commentator in international media (CNBC, Reuters, FT, BFM TV, France 2, etc.) and a speaker at international events (COP22, MENA Investment Congress, Paris Global Conference, etc.).

![Forex Club – Tax 9 – Settle tax on a foreign broker [Download the Application] Forex Club - Tax 9](https://forexclub.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Forex-Club-Podatek-9-184x120.jpg?v=1709046278)

![Trading View platform – solutions tailored to the needs of traders [Review] trading view review](https://forexclub.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/trading-view-recenzja-184x120.jpg?v=1709558918)

![How to connect your FP Markets account to the Trading View platform [Guide] fp markets trading view](https://forexclub.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/fp-markets-trading-view-184x120.jpg?v=1708677291)

![How to invest in ChatGPT and AI? Stocks and ETFs [Guide] how to invest in chatgpt and artificial intelligence](https://forexclub.pl/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/jak-inwestowac-w-chatgpt-i-sztuczna-inteligencje-184x120.jpg?v=1676364263)

![Izabela Górecka – “Success on the market depends not only on knowledge, but also on emotional stability” [Interview] Izabela Górecka - interview](https://forexclub.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Izabela-Gorecka-wywiad-184x120.jpg?v=1713870578)

![WeWork – the anatomy of the collapse of a company valued at $47 billion [WeWork, part II] wework bankruptcy story](https://forexclub.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/wework-bankructwo-historia-184x120.jpg?v=1711729561)

![Adam Neumann – the man who screwed up Softbank [WeWork, part AND] adam neumann wework](https://forexclub.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/adam-neumann-wework-184x120.jpg?v=1711728724)

![The most common mistakes of a beginner trader - Mr Yogi [VIDEO] Scalping - The most common mistakes of a beginner trader - VIDEO](https://forexclub.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Scalping-Najczestsze-bledy-poczatkujacego-tradera-VIDEO-184x120.jpg?v=1711601376)

![Learning patience: No position is also a position - Mr Yogi [VIDEO] Scalping - Learning patience - No position is also a position - VIDEO](https://forexclub.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Scalping-Nauka-cierpliwosci-Brak-pozycji-to-tez-pozycja-VIDEO-184x120.jpg?v=1710999249)

![When to exit a position and how to minimize losses - Mr Yogi [VIDEO] Scalping - When to exit a position and how to minimize losses - VIDEO](https://forexclub.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Scalping-Kiedy-wyjsc-z-pozycji-i-jak-minimalizowac-straty-VIDEO-184x120.jpg?v=1710336731)

Leave a Response