Argentine crisis - tango with debt and bankruptcies

Argentina has been struggling with economic problems for decades. This is an example of a country that proves that nothing is given forever. At the turn of the 1995th and XNUMXth centuries, this country was one of the most developed economic areas of the world at that time. Interestingly, Poles looking for a chance to improve their standard of living chose Argentina as one of the main directions of emigration. As a result, they have become one of the largest immigrant groups in the region. Since XNUMX, the Day of the Polish Settler has been established - "Día del Colono Polaco". The holiday is established every June 8. However, Argentina's former glory is long gone.

Avenida de Mayo, Buenos Aires (1915). Source: Wikipedia.org

For many years, the country has been mired in problems with inflation, an unstable economy and changing political agendas. Argentina returned to the top of the economic press in 2022 due to another risk of bankruptcy. In January 2022, he received another aid from the International Monetary Fund (over $ 40 billion). Argentina has filed for bankruptcy 8 times throughout its history.

It is a country torn by numerous political tensions. Between 1930 and 1977 there were 6 military coups. Political instability meant that Argentina often went "wall to wall". The years of nationalized Peronism were interrupted by periods of violent liberalization. Very often, periods of "little boom" were interrupted by violent recessions. The most famous event in the country's economic history was the crisis at the turn of the XNUMXth and XNUMXst centuries. Its consequences were so great that to this day a large part of Argentinean society is negative about the International Monetary Fund. However, to understand what happened at the end of the nineties of the twentieth century, you need to know the history of this extremely interesting country.

The Argentine Crisis - a history of development and decline

Golden years

After gaining independence in the second decade of the nineteenth century, Argentina was an economically backward country. it was a country with an agricultural and raw material profile. From the eighties of the nineteenth century, there was a rapid economic development of the country. The main investors were the British, but over time more and more capital came to the country from the United States. Mainly thanks to British capital, there was an expansion of rail communication and the development of numerous industries. Argentina gained its comparative advantage in agriculture. To this day, Argentine beef is synonymous with quality. The greatest economic boom lasted from 1880 to the beginning of the First World War. At that time, the average economic growth was around 8% per year. This encouraged the emigration of poor European citizens to this country. The main directions of the influx of immigrants at that time were Italy and Spain. Despite the growing population, economic growth was faster than population growth. The life improvement was stunning. Suffice it to mention that in 1880, Argentina's GDP per capita was 35% of that in the United States. In 1905, Argentina had a GDP per capita of 80% of the United States. Economic development needed machine parts, raw materials and licenses. These were mainly supplied by Great Britain. Imports were covered by exports of agricultural products and industrial products. Argentina has earned its nickname “El granero del mundo”, that is, the barn of the world.

The first problems

After World War I, the inflow of investments slowed down. This was due to the huge losses in European economies due to the war. Even so, Argentina was still one of the most developed countries in the world. The madness of the XNUMXs also contributed to the "little boom" of the economy. Development paused Great Depression. As a result of the crisis, agricultural commodity prices have dropped significantly. Foreign investments dropped significantly. These two factors caused a collapse in exports and an increase in unemployment. The 30s were a period of increasing political unrest. Politicians associated with military circles were increasingly coming to power. Nevertheless, the standard of living of the Argentines was still very high. Per capita GDP was around 60% of the US.

Peronism and anti-peronism - destabilization of Argentina

At the end of World War II, he had more and more political influence Juan Perónwho in 1946 became the new president of Argentina. It was a period of developing social policy and limiting the activities of the opposition. Platform did not take sides in the Cold War. At the same time, he significantly reduced economic freedom in his country. He nationalized the railroads that had so far belonged to French and British companies. In addition, numerous banks, industrial plants and even a merchant fleet were nationalized. Peron has permanently introduced the so-called peronism. Most of the presidents who won the elections in Argentina were supporters peronism. Her views could be characterized in three sentences: social justice, economic independence i political independence. It was an ideology that sought to create a welfare state, increase the state's share of the economy. At the same time, there was an anti-American and anti-British strong point in Peronism. The effect was, among others the expropriation of "Western" investors from the Argentine economy. At the same time, "prosociality" did not mean freedom of opinion. During his presidency, Peron introduced a new constitution that significantly restricted press freedom and introduced a quasi-authoritarian regime. At the same time, the party proclaimed itself to be "the will of the people" and that it was against the establishment. Even though Juan Peron was deposed in 1955. He took refuge in Francoist Spain. With time, there were repressions against the Peronist movement. The political situation continued to be unstable and corruption was booming in the country.

Peron returned to power in 1973 becoming the 41st president of Argentina. After his death, the office of president was taken over by his wife - Isabel Perón. However, already in 1976 it was overthrown by the military. For the next 6 years, a military junta ruled, which fell as a result of losing the war with the United Kingdom over the Falklands. Years of Peronist rule and the military junta, political instability, and pressure on "Fair sharing of the fruits of economic growth" caused a problem with inflation, debt and the level of development of the country. The situation was also not improved by the oil shocks, which also contributed to the economic problems. Argentina's distance from the most developed countries in the world continued to deepen. However, the erosion of Argentina's economic potential has been slow but noticeable. In the period from 1950 to 1980, GDP per capita ranged from 40-50% of the US level.

Democratization and economic liberalism

Carlos Menem. Source: Wikipedia.org

In 1983, Argentina returned to democracy and began the process of marketization of the economy. There was a period of political stabilization. He was elected president twice Carlos Menemwho ruled from 1989 to 1999. He was the longest-serving president in Argentina's history. The new president of Argentina and Congress had to face enormous economic problems. The country has experienced very high inflation and budget problems. At the same time, the instability of the currency and the not very business-friendly law caused investors to avoid Argentina in a wide berth. It is worth adding that the country's economy was relatively closed to trade with the environment. In such conditions, it was decided to introduce the peso exchange rate pegged to a stable currency.

Introduction of a currency board

To stabilize the currency, a currency board was introduced. It meant that The Argentine peso has been pegged to another currency. To encourage foreign capital to invest, the choice fell on the US dollar. Thanks to the currency board, investors did not have to worry about the exchange rate of the Argentine pesa. This made it easier to calculate the profitability of a given investment. At least in theory, the chamber also enforced a reasonable fiscal and monetary policy. In addition to the currency board a number of acts deregulating the markets were introduced and the privatization process started. Opening to world trade and the inflow of investments resulted in a small economic boom. The average GDP growth in 1991–1998 in Argentina was around 6%. At the same time, the problem of hyperinflation was averted. Low inflation, dynamic economic development and a currency stable against the dollar were a good combination. There was a significant improvement in the standard of living of the Argentines. Argentina came to be called the "Latin Tiger". At the same time, the country began to be portrayed as "Prodigy of the Washington consensus".

Unfortunately, not everything was working properly. The increase in imports resulted in an outflow of dollars. Government spending was financed by a deficit, which made it difficult to maintain a pegged peso-to-dollar exchange rate. At the same time, corruption was spreading, causing government funds to be inefficiently invested. Years later it turned out that many famous personalities at the interface between politics and the economy were involved in money laundering and its removal to tax havens. Maintaining the link with the dollar meant that the monetary policy could not be adjusted to regional conditions. As a result, Argentina's central bank could not operate independently. This would not be a problem only if Argentina and the United States had a similar level of development. However, the situation was radically different. The difference in economic development between the two countries was very large. Another problem was that the United States was not Argentina's main trading partner. As a result, a fixed exchange rate could not be an element regulating trade. For example: an increase in imports in the case of a floating currency should result in a currency depreciation (ceteris paribus). This increased the imbalance in foreign trade, but the problem was ignored. However, critics' voices were silenced by graphs of economic growth and low inflation.

Increase in debt and overvaluation of the peso

A fixed exchange rate encouraged governments, local governments and businesses to take out loans denominated in dollars or other most liquid currencies in the world. Thanks to this, they could receive a low interest rate. Of course, the companies most at risk were importing a lot or operating exclusively on the local market. The sudden devaluation of the peso could cause trouble for all major actors in any economy: the state, entrepreneurs and banks. It is worth mentioning that at the end of 2001, only 3% of public debt were loans taken in pesos. So keeping the peso stable was an issue "Live or not live" for the finances of the Argentine government. At the same time, according to the regulations, ⅓ of the monetary base was covered not by dollars but by government bonds denominated in dollars. This was an additional risk factor as government liabilities would be difficult to settle in the event of problems with keeping the peso against the dollar. In an emergency, investors feared that the currency regime was unsustainable for fiscal reasons. A currency devaluation would increase the risk of a country's default.

The situation was also made more difficult by the cheerful fiscal policy of the Argentinian government. In times of prosperity, the government spent more money, and instead of generating a primary surplus, it still had a budget deficit. It was a pro-cyclical action. Therefore, in the event of an economic downturn, the government will be forced to introduce austerity policy - that is, it will apply measures that deepen the crisis. The deficit was partly due to an overgrown public sector. Before the crisis, as much as 12,5% of the workforce was employed in public positions. For comparison, in Brazil and Chile the rate was 6%. It should be noted that in the public sector, much more was paid than in the private sector. In 1994, the salaries in the "row" were 25% than in "privateers". In 1998, the difference was already 45%. The situation was aggravated by the fact that the debt was mostly denominated in foreign currencies. Thus, it was not possible to get the debt paid off through inflation. Inflation would put pressure on the devaluation of the peso against the dollar. In 2000, debt denominated in foreign currencies amounted to 50% of GDP.

Another problem was the current account deficit persisting through most of the nineties. It was a negative trend. First, it increased Argentina's dependence on the influx of foreign capital. Secondly, the current account deficit put pressure on the peso to weaken. Since the peso against the dollar was kept artificially stable, the deficit caused the peso to revaluate. Between 1990 and 2000, the real effective exchange rate (REER) increased by more than 75%. There were a number of factors in the late 90s that made the peso overvalued. The most important of these was the strengthening of the dollar against the European currencies and the devaluation of the Brazilian real. According to the BCRA, in 1999 the peso was overvalued by at least 70%.

The reason that was supposed to increase the scale of the crisis was blamed by many International Monetary Fund. One of the allegations was the pro-cyclical behavior of the IMF. During the boom, the IMF encouraged the maintenance of the currency board, while during the crisis, the fund began to reduce its financial support. Another problem was that the International Monetary Fund turned a blind eye to Argentina's failure to meet fiscal targets. For example: after 1995, despite the rapid economic growth, the IMF did not force the reduction of the deficit level. Exceeding the admissible thresholds did not entail any sanctions against Argentina.

Monetary crisis

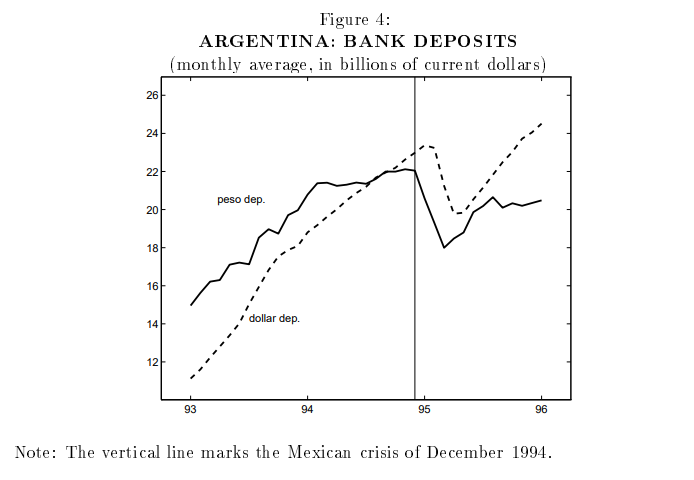

Before the outbreak of the crisis, investors were confident about the stability of the Argentine economy. This was due to the peaceful transition of the Mexican crisis in 1995. Crisis in Mexico caused the so-called "Tequila effect", i.e. a sudden outflow of capital from Latin America. In Argentina, there has been a sharp outflow of dollar deposits from banks. It amounted to over $ 8 billion, which accounted for less than 18% of all deposits. At the same time, the level of liquid reserves of foreign exchange reserves in the Central Bank of Argentina decreased by 30%. The outflow of capital also hit the stock market. The MERVAL index at the peak of the panic fell by almost 50%. The market shock caused that the GDP in 1995 fell by 2,8%, while the level of investments decreased by 13%. However, the economy recovered very quickly. In 1996, GDP grew by 5,5%. For this reason, many investors believed that the Argentine economy was one of the most resilient in all of Latin America. However, it is worth noting that Mexico's monetary crisis has led Argentines to prefer to hold their deposits in dollars rather than pesos.

1998 - 1999

In Argentina, it began to take shape a dangerous mix of monetary and fiscal threats. However, the problems were hidden under the veil of good economic performance, improved living standards and a stable banking system. For this reason, more attention was paid to "less stable" Brazil, which had more visible effects of economic imbalance. Speculators took advantage of this and started playing against the Brazilian central bank. As a result, the real exchange rate was unsustainable in the current fluctuation band. This caused the real value to drop significantly. This indirectly hit the Argentinean economy, which was tied to the dollar and was unable to react. This lowered the competitiveness of the Argentine economy in the world markets.

Another problem was the changing market environment. As a result of a series of crises in developing markets, the US dollar (which also peso) strengthened. At the same time, external shocks appeared in the form of:

- the Asian crisis

- the Russian crisis

- the fall of the LTCM

- devaluation of the peso

As a result, the economic situation in Argentina deteriorated from mid-1998. The expected rapid return to economic growth did not take place. As a result, some economists and investors began to worry about the stability of the currency board system in Argentina. The slowdown meant that tax revenues (and so ineffectively collected) decreased. At the same time, interest costs remained unchanged and the budget deficit remained large. The Argentine government needed additional funding. In December 1999, President Fernando de la Rua began seeking help from the IMF. Three months later, an agreement was signed between Argentina and the International Monetary Fund. Argentina signed a 3-year stand-by deal worth $ 7,2 billion. In return, the country was to begin the process of introducing a more restrictive fiscal policy. Argentina cut government spending by $ 1,4 billion in 1999. It was supposed to be a signal that the government was serious about improving the budget situation.

Corralito and Cacerolazo

In 2000, there were further reductions in spending (by $ 900 million) and a rise in taxes by $ 2 billion. Such a policy had a negative impact on economic growth. The government tried to save by further freezing spending and lowering pensions. However, deteriorating market sentiment made Argentina struggling to find financing in the market. Fiscal and monetary problems were noticed by Standard & Poor's, which in November 2000 began to monitor Argentina's debt-financing capacity more closely. In June 2001, it downgraded the rating to B-. In 2001 Cavallo proposed the so-called megacanje ("magaswap"), which involved the conversion of short-term bonds into higher-interest bonds with a longer maturity. As a result, Argentina was able to defer payments of $ 30 billion (payable until 2005) in exchange for 14% interest. It was a peculiar act of despair and an attempt to postpone the inevitable in time. At the same time the Argentine government continued the policy of tightening the belt (austerity), by reducing employment in government agencies and by limiting some government spending (including social transfers). In July 2001 the unemployment rate was 14,7%, in December 2001 it increased to 20%.

Economic problems translated into a government crisis. The De la Rua party lost its majority in parliament. As a result, investors were concerned about the country's political stability. The scale of disenchantment with the political system in Argentina was so great that around 20% of the ballots were invalid or empty. The situation was also worsened by the IMF's decision to withhold the payment of the $ 1,3 billion tranche of the loan. The reason was the "failure to keep promises" by the Argentine government. The IMF called for major budget cuts. In December 2001, the market panic caused the prices of Argentinian bonds to drop dramatically. This caused Argentina's dollar bonds to be traded at a huge discount to the US government bond. The difference in the interest rate (yield) was 11 percentage points on December 42. The market expected a large reduction in debt in the home of tango. At the end of 2001, Argentina suspended the service of its foreign debt worth more than $ 82 billion.

Cacerolazo Buenos Aires December 20.12.2001, XNUMX. Source: Wikipedia.org

Economic problems and the ongoing currency crisis made people lose confidence in the peso. As a result, from the end of November 2001, the phenomenon of a massive withdrawal of dollar amounts from banks and the exchange of pesos into dollars began. Wealthier citizens transferred funds to foreign banks. It was a classic bank run. This added to the instability of Argentina's already fragile financial system. In effect The government, on December 2, 2001, prohibited the withdrawal of more than 250 pesos per week (ie $ 250) from a bank account. Informally, this ordinance was called corralito (pl. playpen). The journalist Antonio Laje is considered to be the author of this term.

The government's action prompted the Argentinians to start protests in the streets. Initially, they took the form of high-profile demonstrations, where the protesters hit metal pots and pans (the so-called casserole). After some time, the peaceful protests turned into incidents of property destruction. Outlets of banks or private companies owned by American or European investors were particularly at risk. Eventually there was a tragedy. Between 20 and 21 December, there were clashes between protesters and the police in the Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires. As a result of the incident, several people lost their lives. This resulted in the collapse of the De la Rua government. 2001 ended with a GDP decline of 4%. However, the crisis continued.

2002 - the height of the crisis

Due to the impossibility of maintaining such an overvalued peso, the fixed exchange rate was abandoned in January 2002. The official rate was set at 1,4 pesos for $ 1. Before the devaluation, the rate was 1: 1. There was also a forced conversion of dollar deposits into pesos at the official rate of ARS 1,4 for $ 1. At the same time, the liabilities were swapped at the rate of 1: 1. This hit dollar savings twice. Inflation peaked in April when prices in the economy rose by 10% month on month. In October, the monthly price increase was around 0,5%. High inflation caused the peso to depreciate. The liberation of the peso and the need to adjust the economy resulted in a sharp decline in the value of the peso. In 2002, the exchange rate hit 4 pesos to 1 dollar. The depreciation of the currency made imports more and more expensive. In turn, high unemployment put pressure on not increasing real wages. This made many imported goods unattainable for many Argentines. Unemployment was still around 20%. In 2002, Argentina's GDP fell by more than 10%.

Stabilization and return to growth

Roberto Lavanga. Source: Wikipedia.org

In May 2003, elections were held to elect President Nestor Kirchner (a supporter of Peronism) for the office. The composition of the government also changed, but the same person became the minister of the economy - Roberto Lavanga. Thanks to his hard work, the foundations of the Argentine economy were improving. With time, this allowed for the withdrawal of funds deposited by bank customers to be lifted.

Slowly, the economic situation began to stabilize. The fall in the value of the peso made exports competitive on world markets again. He helped increase in soybean priceswhich was mainly exported to China.

This improved the trade balance, which made it possible to rebuild the central bank's foreign exchange reserves, which in 2005 reached the level of $ 28 billion. Following the stabilization, the peso exchange rate improved as well, amounting to 3: 1 against the dollar. The central bank made sure that the peso did not appreciate too much. Thanks to this, the export premium was maintained. In the following years, the economic growth measured by the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) ranged between 6% and 8%. Inflation continued to be a problem (until the subrime crisis it was usually more than ten percent annually). On the other hand, unemployment fell, and in 2007 it dropped to 7,8%.

Debt restructuring

Argentina's disregard for its interest obligations resulted in the domestic debt being traded at a fraction of its value. A few years after its insolvency, Argentina sat down to talk with its creditors. It proposed to issue new bonds with a value of 25-30% of the nominal value and with a long repayment period. About 76% of the bondholders (bondholders) agreed to these terms. The contract was signed in 2005. Five years later, a second round of negotiations with creditors followed. After that, 93% of creditors agreed to debt reduction and an extension of the repayment period. The remaining 7% pursued their rights in court demanding repayment of the entire debt.

Summation

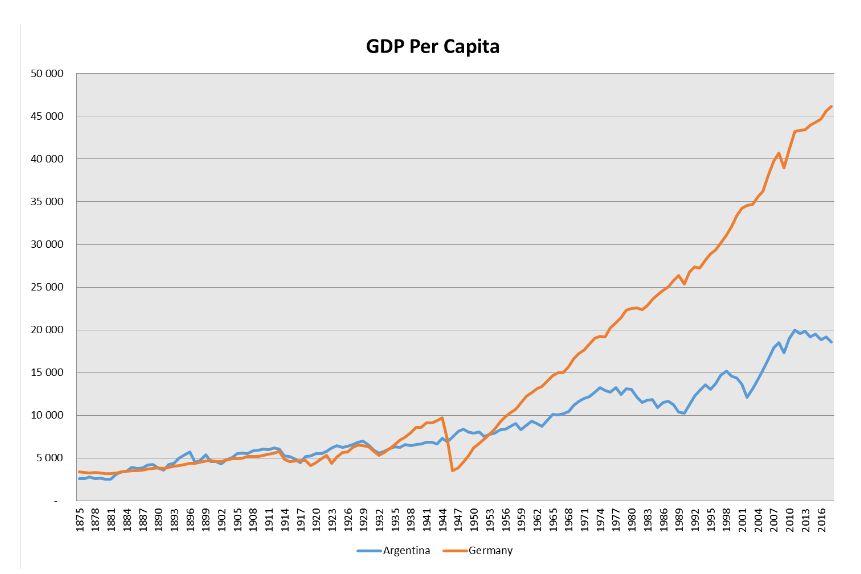

The Argentine crisis was a real tragedy for the country's society. Much of the population began to live below the poverty line. This caused great reluctance by the Argentines to the IMF, neoliberalism, and American and European financial institutions. Argentina's history should be a lesson for rulers and citizens in many countries. Peronism and military rule contributed to the tragedy of economic stagnation and high inflation. On the other hand, the remedy used in the 90s was used selectively because the rulers preferred to postpone difficult reforms for the future. The tango with debt continues in Argentina. Despite the economic development, the country lagged behind the leading economies in the world. This can be seen in the graph below:

Source: Own elaboration based on Project Maddison 2020

![Forex Club – Tax 9 – Settle tax on a foreign broker [Download the Application] Forex Club - Tax 9](https://forexclub.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Forex-Club-Podatek-9-184x120.jpg?v=1709046278)

![Trading View platform – solutions tailored to the needs of traders [Review] trading view review](https://forexclub.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/trading-view-recenzja-184x120.jpg?v=1709558918)

![How to connect your FP Markets account to the Trading View platform [Guide] fp markets trading view](https://forexclub.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/fp-markets-trading-view-184x120.jpg?v=1708677291)

![How to invest in ChatGPT and AI? Stocks and ETFs [Guide] how to invest in chatgpt and artificial intelligence](https://forexclub.pl/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/jak-inwestowac-w-chatgpt-i-sztuczna-inteligencje-184x120.jpg?v=1676364263)

![WeWork – the anatomy of the collapse of a company valued at $47 billion [WeWork, part II] wework bankruptcy story](https://forexclub.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/wework-bankructwo-historia-184x120.jpg?v=1711729561)

![Adam Neumann – the man who screwed up Softbank [WeWork, part AND] adam neumann wework](https://forexclub.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/adam-neumann-wework-184x120.jpg?v=1711728724)

![How to transfer shares to another brokerage office [Procedure description] how to transfer shares to another brokerage house](https://forexclub.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/jak-przeniesc-akcje-do-innego-biura-maklerskiego-184x120.jpg?v=1709556924)

![The most common mistakes of a beginner trader - Mr Yogi [VIDEO] Scalping - The most common mistakes of a beginner trader - VIDEO](https://forexclub.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Scalping-Najczestsze-bledy-poczatkujacego-tradera-VIDEO-184x120.jpg?v=1711601376)

![Learning patience: No position is also a position - Mr Yogi [VIDEO] Scalping - Learning patience - No position is also a position - VIDEO](https://forexclub.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Scalping-Nauka-cierpliwosci-Brak-pozycji-to-tez-pozycja-VIDEO-184x120.jpg?v=1710999249)

![When to exit a position and how to minimize losses - Mr Yogi [VIDEO] Scalping - When to exit a position and how to minimize losses - VIDEO](https://forexclub.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Scalping-Kiedy-wyjsc-z-pozycji-i-jak-minimalizowac-straty-VIDEO-184x120.jpg?v=1710336731)

![WeWork – the anatomy of the collapse of a company valued at $47 billion [WeWork, part II] wework bankruptcy story](https://forexclub.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/wework-bankructwo-historia-300x200.jpg?v=1711729561)

![Adam Neumann – the man who screwed up Softbank [WeWork, part AND] adam neumann wework](https://forexclub.pl/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/adam-neumann-wework-300x200.jpg?v=1711728724)